A Forbidden City restoration project that most Hong Kong people are still unaware of, and a book documenting this restoration process that was published over a decade ago in both an English edition and a mainland simplified Chinese edition—Jianfu Palace: Rebuilding a Garden in the Forbidden City—has now been released in a traditional Chinese edition in Hong Kong. This coincides with the 100th anniversary of the Palace Museum (2025) and the 20th anniversary of the completion of the Jianfu Palace Garden.

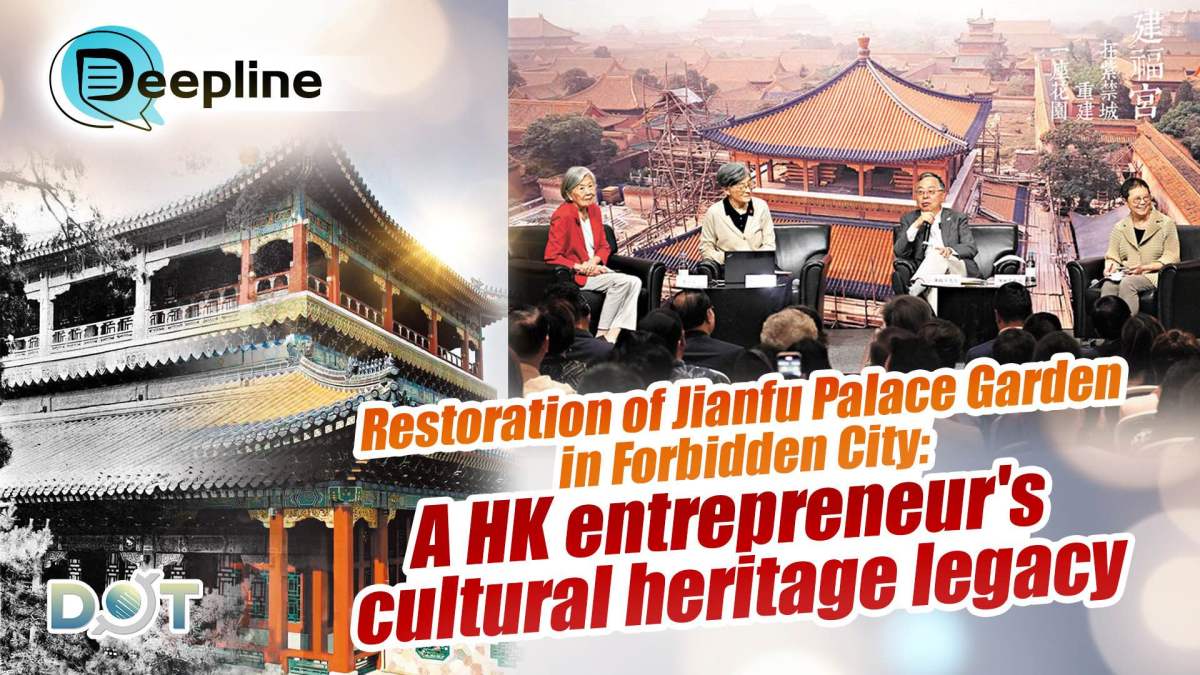

Earlier, at the invitation of Ronnie Chan, founder and Chair of the China Heritage Fund (CHF), hundreds of distinguished guests from various sectors in Hong Kong and the mainland gathered at the Hong Kong Convention and Exhibition Centre (HKCEC). They sat quietly in the audience, listening to a group of individuals involved in the project share the remarkable origins of their participation: a small southern border island whose cession nearly two hundred years ago went unnoticed by the northern emperor; a group of dedicated people living in Hong Kong who care about China's destiny; and this former imperial palace of the Ming and Qing dynasties, now a precious heritage of Chinese culture and world civilization.

The Jianfu Palace Garden, initially built in the seventh year of Emperor Qianlong's reign (1742 AD), is located in the northwest corner of the Forbidden City, behind high walls and deep courtyards. Its layout is compact and intricate, embodying the rich style of traditional Chinese gardens. It served as a place of leisure and entertainment for Emperor Qianlong and also housed numerous rare treasures. Unfortunately, a mysterious fire on the evening of June 26, 1923, reduced this magnificent imperial garden to ashes overnight, along with countless antiques, calligraphy, paintings, and artistic treasures. This is the only ancient architectural site within the Forbidden City to have been destroyed. This scarred area, hidden within the seemingly opulent Forbidden City complex, remained silent for nearly a century due to years of political turmoil and national weakness.

It was not until the emergence of Ronnie Chan, who is dedicated to the restoration of China's ancient architectural heritage. He visited the site of the Jianfu Palace Garden in 1994, established the China Heritage Fund in Hong Kong in 1999, and in 2000, the foundation collaborated with the Palace Museum to initiate the site's restoration project.

This thematic lecture was hosted by three main speakers, including Ronnie Chan and the author of the book, May Holdsworth, who simultaneously documented the entire restoration process, along with Professor Ying Chan of the University of Hong Kong. The protagonists were, of course, these individuals who personally participated in the entire process. Their inspiring shares were captivating, with the audience sometimes listening in rapt silence and at other times responding with warm applause as a mark of respect.

Returning to the Jianfu Palace Garden project, Professor Chan said in her opening remarks: This is the largest restoration project since the establishment of the Palace Museum in 1925, setting many "first" records: the first restoration project approved by the State Council; the first time the Palace Museum accepted non-governmental funding; the first time the Palace Museum attempted such a large-scale restoration project; the first collaboration between the Palace Museum and a non-governmental organization. Thus, this historic project achieved the "only 'ancient architectural' complex rebuilt within the Forbidden City."

A complete Forbidden City

"The destruction of cultural relics is clear evidence of a nation's decline; while the restoration of cultural relics is solid proof of a nation's revival." This is the idea that still lingers in Ronnie Chan's mind after 30 years of involvement in cultural heritage conservation. As early as the first half of the 1990s, he conceived the idea of protecting ancient architectural heritage in the mainland.

Initially, Ronnie Chan had no intention of doing heritage conservation in Beijing. "My idea at the time was, definitely don't do it in Beijing. Beijing is a political center; it's too complicated; we should go to remote places far from the emperor." It wasn't until a British friend mentioned that there was a site in the Forbidden City that had been destroyed by fire. In 1994, Ronnie Chan entered the Jianfu Palace site within the Forbidden City for the first time: "a wasteland, overgrown with weeds, with a dilapidated small wooden boat discarded nearby." His feeling was: this was a portrayal of the nation's fate of decline over the past two hundred years. From this, Ronnie Chan developed a strong desire: to restore the Jianfu Palace Garden and return a complete Forbidden City to the nation.

However, there were also differing views at the time. Some believed the site should be preserved as it was, serving as a poignant historical testimony. Ultimately, the State Council made the decision, confirming the restoration plan. Ronnie Chan adhered to several principles already established and observed in the global heritage field, the most basic of which was: use the "original design, original materials, original methods" as much as possible.

"What I hope to leave for the nation is not just an architectural complex that looks the same as the original, but also professional restoration project management. Both software and hardware are equally important."

In terms of hardware, the Palace Museum brought in stonemasons from generations-old families. The foundation also hired foreign experts to teach stone restoration techniques. "Chinese people know how to build and how to rebuild after destruction, but generally lack the practice of preserving the old on a partially damaged basis and matching it with new elements to restore the original appearance."

"Basically, our compatriots lack the concept of preserving existing traces. For example, if a stone base is half burnt, they remove the remaining half and start over. That's really a pity." Ronnie Chan said, "Without respect for the old, the new becomes meaningless." The donation from the China Heritage Conservation Foundation for this project was the largest donation the Palace Museum had received at that time. Ronnie Chan is sincerely proud of being able to participate in such a grand endeavor. "Fortunately, we saw it early. If it were now, how could we have such a good opportunity to participate? Chinese civilization is also part of human civilization."

Introducing systems into cultural heritage conservation industry

However, thinking that the foundation's role was merely providing funds would underestimate the difficulty of doing things in China during the transition period, especially in the extremely closed or conservative field of cultural heritage conservation. In the publication's preface, Ronnie Chan wrote: "Money is actually the least valuable. Admittedly, we are not experts in ancient architecture, nor do we have a construction team. The most qualified in this regard is our partner, the Palace Museum. What the foundation brought to the entire project, most importantly, was management."

For example, the foundation insisted on signing a formal construction contract with the Palace Museum, making it compliant at the legal level. The foundation also hired world-class quantity surveyors to conduct third-party assessments of the project's progress and quality before the foundation made payments. Safety and cleanliness at the construction site were also required to meet international advanced standards. The entire restoration process was documented with video or photographs as much as possible.

Ronnie Chan attempted to introduce the then-unfamiliar norms of rigorous work systems and the corresponding cultural concepts behind them into the cultural heritage conservation industry, which was predictably difficult in the early stages. This also reflects the theme revealed by historian Ray Huang in his famous book 1587, A Year of No Significance: the lack of "mathematical management" in Chinese culture. Using the administration during the Wanli era of the Ming Dynasty as an example, he described the conceptual and institutional challenges that hinder organizational development. To some extent, similar problems existed in the restoration of Jianfu Palace.

When the restoration project was finally completed in 2005, it is said that Ronnie Chan declined the museum's kind offer: "We absolutely must not erect a statue or plaque for ourselves. Personal names should not appear in the imperial architectural complex. After completion, hand it over to the Palace Museum; fulfilling the wish of doing something meaningful for Chinese civilization is enough."

(Source: Wen Wei Po; Journalist: Jiang Hu; English Editor: Darius)

Related News:

The Palace Museum in a Minute EP1 | The Nine-Dragon Wall【The Palace Museum Centennial】

Comment