By Liu Yu

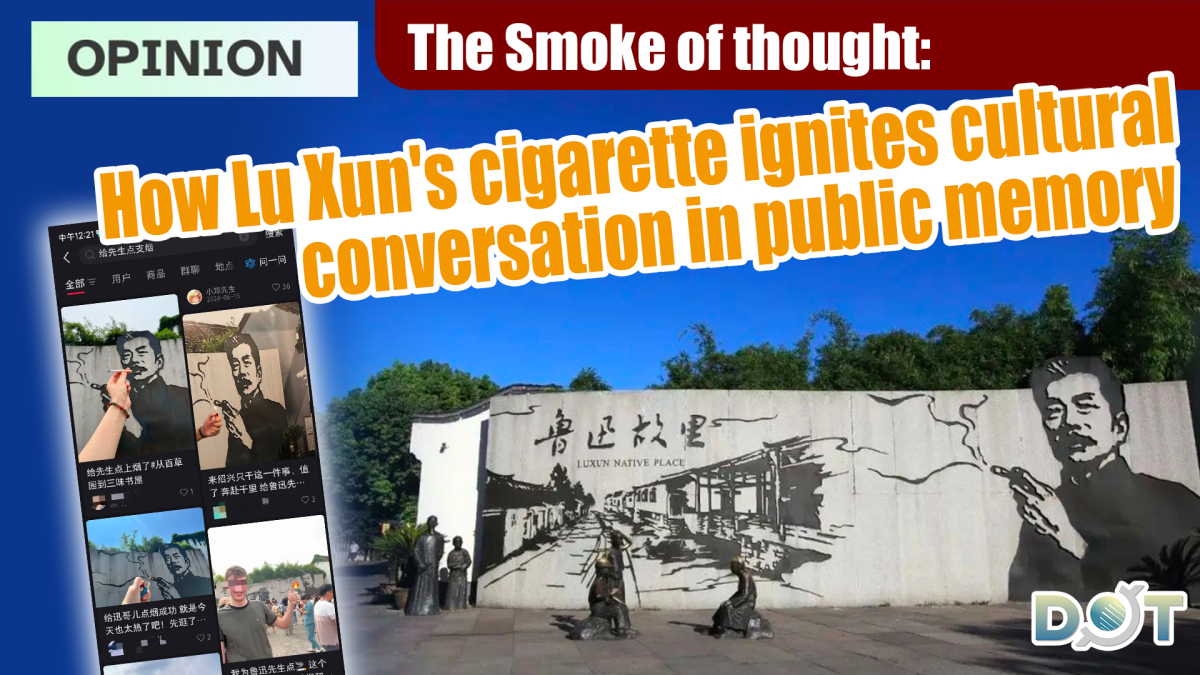

Recently, a wall painting at the Lu Xun Memorial Hall in Shaoxing, Zhejiang, depicting the writer holding a cigarette, has become a focus of public debate. Some visitors expressed concern that such an image might have a negative influence on adolescents, quickly propelling the topic to trend online and sparking widespread discussion.

On August 25, the Shaoxing Municipal Bureau of Culture and Tourism responded, stating that they had received feedback from the public across the country, with the majority believing that the mural presents an objective historical fact and has become an important cultural symbol of Lu Xun's hometown. They emphasized the need to respect history and avoid making hasty changes based on individual complaints. The bureau stated that it would gather broad public opinions before making a decision, noting that "whether to modify the mural has not been finalized and will be carefully determined after a comprehensive evaluation."

The relationship between Lu Xun and smoking was not merely a personal habit but also an integral part of his literary identity and spiritual demeanor. He once described his three indispensable daily actions as "lying down, lighting a cigarette, and picking up a pen," smoking up to fifty cigarettes a day. This detail is far from an insignificant fragment of his life; rather, it serves as a window into understanding his creative state and inner world.

From a broader literary perspective, the act of smoking carries rich symbolic meanings across different cultural contexts. In European and American literature, it often metaphorically represents rebellion and alienation—for instance, Santiago's cigarette in Hemingway's The Old Man and the Sea symbolizes an indomitable spirit, while characters in Sartre's Nausea use smoking to confront absurdity, and Meursault in Camus's The Stranger employs smoke to isolate himself from worldly hypocrisy.

In Japanese literature, smoking is woven into the aesthetic expressions of "mono no aware 物哀" (the pathos of things) and "nihilism 虛無"—Yasunari Kawabata's Snow Country intertwines smoke and snow to capture fleeting beauty, and smoking scenes in Haruki Murakami's works serve as tiny rituals for urban dwellers combating confusion.

In Chinese literature, smoking often reflects the era and human nature—Lu Xun's The True Story of Ah Q uses "smoke" to depict the spiritual plight of the lower class, the transformation of Xiangzi's smoking in Lao She's works symbolizes shattered hopes and the alienation of humanity, while Wang Zengqi uses it to convey the warmth and simplicity of folk life.

The Zhejiang Lu Xun Research Society has also taken a clear stance on this issue, opposing the online sensationalism surrounding the topic of "Lu Xun smoking" and emphasizing that the "everyday image of Lu Xun" presented by the mural is deeply rooted in historical authenticity and cultural identity. Secretary-General Zhuo Guangping pointed out that it is inappropriate to mythologize Lu Xun or confine him to a combative posture, noting that his smoking image instead helps the public understand his true, human side. The association further criticized certain online behaviors for chasing traffic and jumping out of the discourse, which does little to promote the legitimate dissemination of Lu Xun's spirit. It also highlighted that the mural, as a decades-old iconic landmark, would represent a disrespect for history and art if removed due to a single controversy, and such a move would be unlikely to gain public acceptance.

This controversy extends far beyond whether to retain a wall painting; it fundamentally involves deeper reflections on how we understand history, interpret culture, and approach art. Lu Xun's image is not one-dimensional—his greatness lies not only in the sharpness of his literature and the depth of his thoughts but also in the traces of his flesh-and-blood existence. In the dialogue between public memory and contemporary values, what is needed is a calm and dialectical attitude: one that respects historical truth and context while maintaining an open interpretation of artistic symbolism, thereby forging a more nuanced path to understanding between symbols and meanings, and between figures and their eras.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of DotDotNews.

Related News:

Opinion | From Lugou Bridge to the parade ground: Historical memory must not end in ceremony

Opinion | Medical myths and political manipulation: West's final move in Jimmy Lai trial

Comment