By J.B.Browne

In her latest exhibition, Hong Kong artist Riya Chandiramani reimagines the gender and form of traditional cereal box characters.

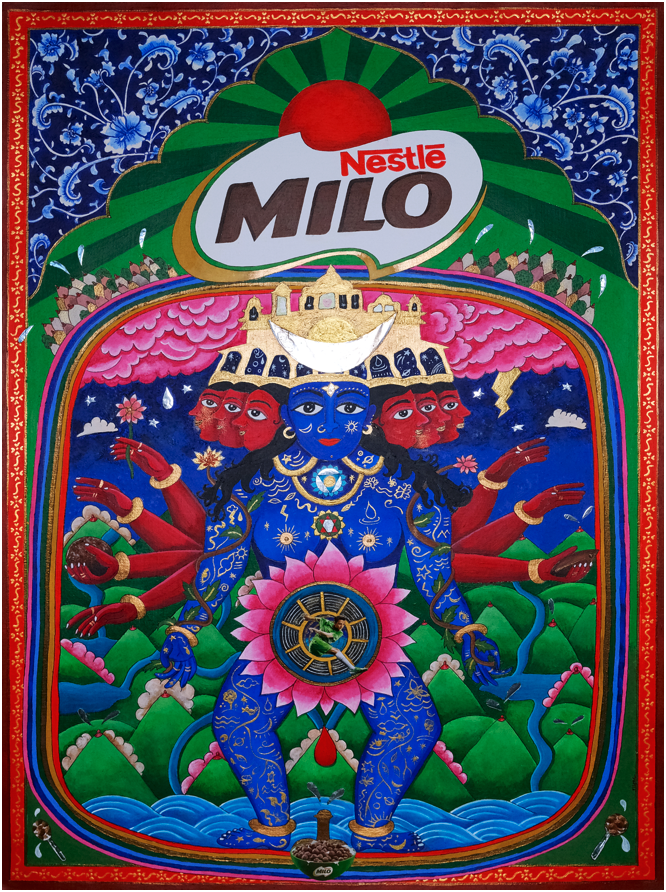

Balls In Her Court

Mixed Media on Paper

16.5 x 23.4 in

"In my hungry fatigue and shopping for images, I went into the neon fruit supermarket."

-Allen Ginsberg, "A Supermarket in California," 1955

When was the last time you took a long hard look at your cereal box? The swirling bright colors; the quirky mascots armed with catchphrase and jingle; the hypnotizing mascot eyes that stare right through you; the bold, bouncy fonts, screaming for attention — a box to be held and cherished. When you were a kid, you wanted it, needed it. You pointed at the shelf and asked your parents to chuck it in the shopping basket.

The psychology of cereal boxes is something else. Fun, whimsical, and appealing to children on the outside — the sugar coating; but deeply psychological and manipulative on the inside — the nutritional value or lack thereof. Whether puffed, baked, or flaked, some snap, crackle, pop ain't the healthiest thing to put in your body. Too much can lead to weight gain flanked by bonus tooth decay and high blood pressure.

When we think about advertising, we may define it as a form of communication that draws attention to ideas, goods or services, or even a brand itself. Advertising through mass media is never much targeted to individuals but groups. When researchers at Cornell University's Food and Brand Lab did a study in 2014 on cereal box psychology, they found that box designs directly appealed to and were marketed towards children where even the height and the angle the cereal characters "looked down" at the young and impressionable.

But there's more. Largely male-dominated characters play leads to the secret manipulation of emotions within the box designs. And if children are targeted as such to be manipulated subconsciously, what are the implications of subtexts influencing their perceptions of others?

In the 2009 article, Gender and Form of Cereal Box Characters: Different Medium, Same Disparity, a study found that out of 217 cereal boxes, 82% had male mascots on the front with only 18% female. The study also discovered that adult animal characters were universally male, whereas female characters get portrayed as children.

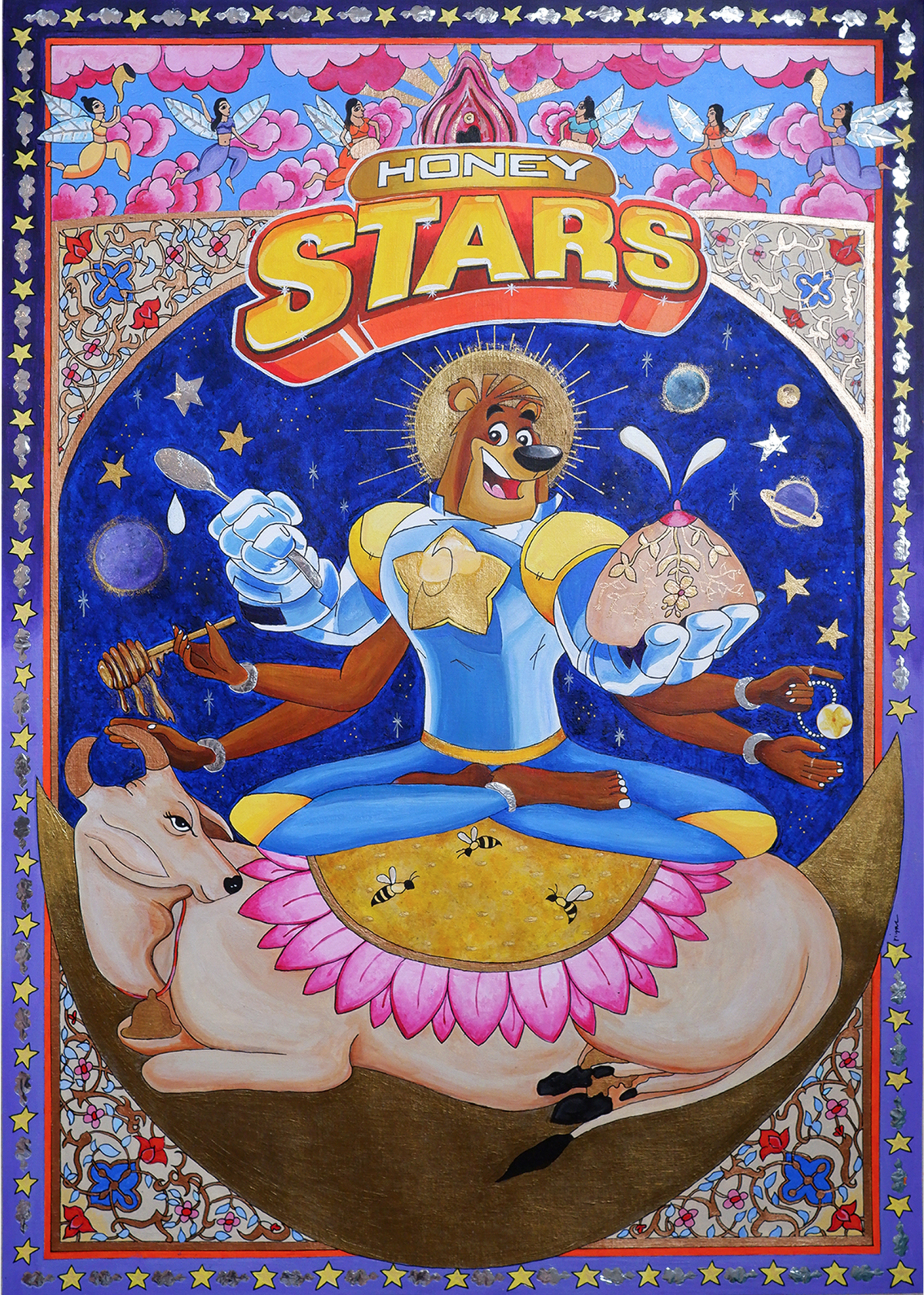

The tension between seduction and oppressive manipulation of cereal boxes forms the basis of Chandiramani's latest work, The School Pack Series — three pieces highlighting the shocking disparity of flagrantly biased representations of the medium but with playful Hindu iconography and the artist's signature "breast mountain."

"But I love cereal," she says cheerily, recalling the moment a friend told her she thought of cereal when she thought of her. The concept came quickly. The artist, burned out from listless commissions, wanted something for herself – something conveying a strong and meaningful message.

"Given my past, I wanted to do something on nourishment, the body, and women," she says bravely, alluding to an eating disorder and sexual assault during college. Over zoom, Chandiramani consistently fires off refreshing moments of insight and honesty, carrying a wisdom beyond her 27 years.

I'm In Love with The Koko

Mixed Media on Paper

16.5 x 23.4 in

Born and raised in Hong Kong, Chandiramani has always maintained a solid connection to her Indian heritage, mainly through her parents and immersion in Indian art. In some respects, Chandiramani's art is no different from many 'homegrown' Hong Kong artists who mine the city's East/West culture clash for inspiration but also bring something of themselves.

Each of the three pieces in the school pack contains three stylistic elements. The first is the artist's obsession with Indian miniature paintings from the Mughal and Persian schools. The Mughal Empire (1526-1757 AD) saw an increase of art studios at the Imperial court, ushering in a new phase of Indian painting. You can tell this style has besotted Chandiramani since childhood, who describes them as "detailed, colorful, and absolutely gorgeous."

The second element is cereal boxes. For example, the artist uses the holy trinity of southeast Asian cereal brands — Honey Stars, Koko Krunch, and Milo — to stand out against more prevalent Western-American brands. Despite regional manufacture, western branding methods prevail, with all three brands using male mascots.

"It's such a blatant thing when you do look at them," she hums softly, disdainfully.

"But it's something that escapes us all that the lack of representation is there as well for women across multiple cultures."

The third element is the powerful beauty of Mao-era propaganda posters though not for the apparent reasons for criticizing China's system of governance.

"It's less about communism and more a metaphor for how capitalism is," she explains, an air of resigned irony trailing behind her words.

In some ways, capitalism as the ultimate expression of patriarchal oppression cannot coexist with feminism. Sexism and oppression may not have begun with capitalism, but both have undoubtedly been exacerbated by it. And if sexism itself helps to uphold capitalism, well, it starts young with things like male mascot cereal boxes.

Mo Honey Mo Problems

Mixed Media on Paper

16.5 x 23.4 in

By showcasing the individuality of women, Chandiramani chooses to feature strong warrior Hindu goddesses who are maternal life-givers. The artist's signature "breast mountain" features in all three pieces as well – the breast, every breathing child's first form of nourishment, and healthier than sugary cereal.

"I'm trying to remove all the stigma around these like vital life processes," she says.

Long before Instagram, Americans boasted of their travels using German-born printer Curt Teich's cheery linen postcards with the immortal words "Greetings From" emblazoned on the front. For Chandiramani, there's more than a whiff of vintage iconography about her up-and-coming exhibition at the Affordable Art Fair later this month, including the flyer, which reads:

"Greetings from Riya Chandiramani, from the Fragrant Harbour."

The flyer recalls 1960s hippy culture graphic design. But it's the work she's exhibiting that most echos the rebellion of the 1960s psychedelic rock era whose music influenced millions, especially the cover art for Jimi Hendrix's second album, Axis: Bold as Love (1967).

French philosopher and author Albert Camus once wrote an essay called The Rebel. In it, he noted that the artist "rejects the world on account of what it lacks and in the name of what it sometimes is." It's a striking claim about the nature of art.

"I could never exhibit my work in India," Chandiramani says, adding that her safety might be in danger. India is still a male-dominated society, where women are still seen as subordinate and inferior to men.

"You know, I've received enough hate messages on Instagram for my current work by fanatics in India who love their gods and can't bear to see goddesses without clothes on."

Social change is slow, the seeds of which are sown in artistic statements and points of cultural discussion.

Go and see for yourself.

The Fragrant Harbour group show presented by Young Soy Gallery will take place at the Affordable Art Fair (booth A10) between August 26-29 at the Hong Kong Convention & Exhibition Centre.

As he would refer himself, J.B. Browne is a half "foreign devil" living with anxiety relieved by purchase. HK-born Writer/Musician/Tinkerer.

The views do not necessarily reflect those of DotDotNews.

Comment