By Jennifer Zhang

Race has always been a common factor used as a means of categorization of people. By defining groups of people through a set of observable characteristics, classification through race becomes convenient and automatic, but also has detrimental impacts on perception of identity. In recent times, as racial tensions run high as people of color rise to defy racial bias and discrimination embedded in social institutions, it is crucial to deconstruct the concept of race to understand what race represents at its core in order to fully subvert systemic racism and achieve stable equality.

In the study of anthropology, the concept of race has gradually changed and evolved, influenced by increased understanding of the origins of the notion of race and investigation of what the concept of race defines.

In the past, anthropologists interpreted race as a biological phenomenon. Race was defined to be specific and inseparable from one's biology, viewed as a distinct physical quality that is shared among people with the same phenotypic traits, which separated people into different groups. This association of race with biology stemmed from the history of European colonialism and slavery, which became integrated into the early classification of nature from a Eurocentric standpoint, as Ashley Montagu claims in his book The Fallacy of Race, "the modern conception of race is rooted in European colonialism."

Throughout the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, the age of Enlightenment, European exploration and colonization of foreign countries and indigenous peoples influenced greatly how people were biologically classified, where the cursory documentation, ethnocentric and naive in descriptions, of non-European ethnic groups through a reliance on physical characteristics such as skin color contributed to the utilization of skin color as a defining category.

The portrayal of other ethnic groups through a solely phenotypic lens limited European naturalists and taxonomists to classify them through race, shown in the influential works of Linnaeus' Systemae Naturae, proposing four categories of Homo sapiens: Americanus; Asiaticus; Africanus; and Europeanus, and Johann Friedich Blumenbach's race-based classifications in On the Natural Variety of Mankind, categorizing the human race into Caucasian, the white race; Mongolian, the yellow race; Malayan, the brown race; Ethiopian, the black race; and American, the red race.

Racial classification was then solidified by Kant's Theory on Human Variation, grading races according to level of talent, "with Europeans on top, 'yellow Indians' possessing meagre talent, 'Negroes' being far below them, and at the lowest point 'Americans'", creating a sense of superiority and inferiority among races, shaping the racial hierarchy to degrade people of color.

In addition, the rise of slavery reinforced the concept of the racial hierarchy, where in order to justify the subjugation of African slaves, the establishment of the belief that dark skin is inferior provided an ultimate defense for slavery, becoming what Nina Jablonski claims in The Struggle to Overcome Racism, "one of the most powerful and destructive intellectual constructs of all time".

These stereotypical and damaging conceptualizations of race contributed to anthropologists' interpretation of race in the 19th to early 20th century, following the idea of racial essentialism that formed scientific racism, the argument that humans form stable biological subgroups with different mental capabilities which form a hierarchy of higher and lower races.

However, racial essentialism in the study of anthropology was gradually overturned as the scientific investigation of ancestry and genetics led anthropologists to conclude that races are not biological, and are a man-made construct. The first anthropologists to question previous perceptions of race were Franz Boas and Ashley Montagu.

Boas argued against scientific racism by conducting a series of research based on bodily measurements in his work The Instability of Human Types, where he refuted the racist assumption of the stability of human types (not 'races') and the inferiority of some. Boas, through the study and measurement of human skeletal anatomy showed that cranial shape and size was highly malleable depending on environmental factors such as health and nutrition, in contrast to the claims by racial anthropologists of the day that held head shape to be a stable racial trait. This contradiction propelled the argument that all human types are changeable under different circumstances, therefore undermining the theory of biological race and racial hierarchy.

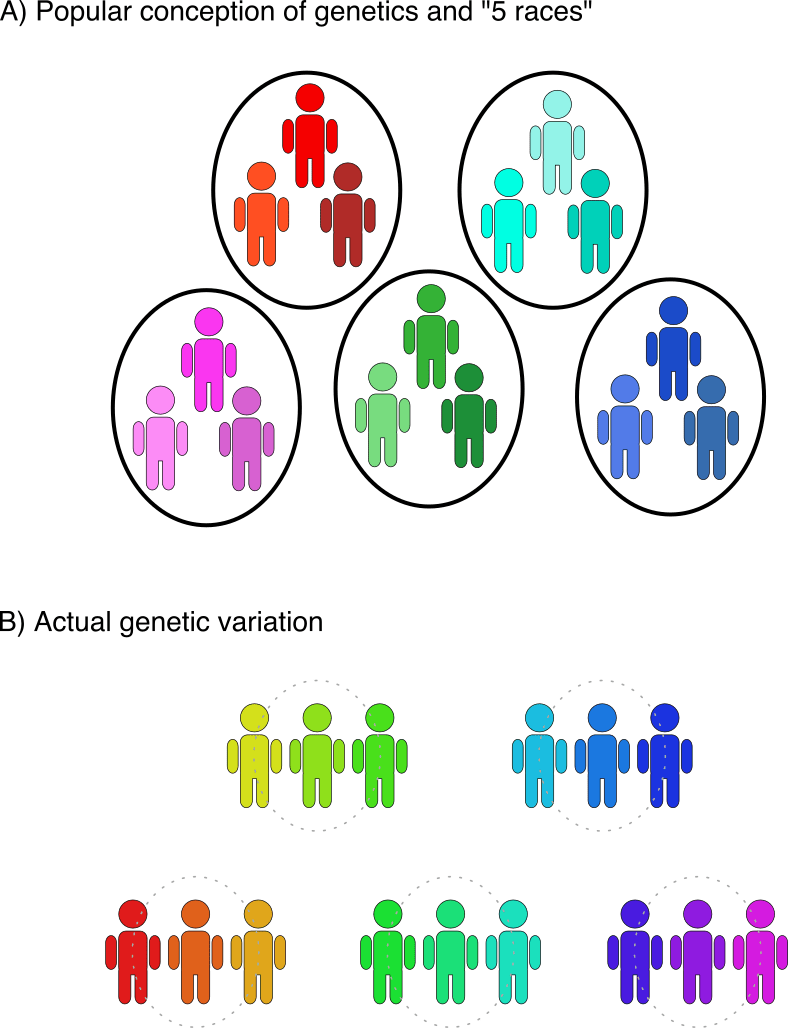

Anthropologist Montagu approached the notion of race through the study of genetics, tracing evolutionary history through molecular genetics, finding evidence that humans in fact diverged from one common ancestor, and that human genetic differences should not be classified through race, but rather is a sign of genetic variability.

With such ideas from Boas and Montagu as the foundations of a new understanding of race, anthropologists began to draw even more evidence negating the association of race with biology, and redefined race to be a biologically non-existent concept. The evolution of human skin coloration clarified that skin colors were a product of the environment humans settled in, where the amount of melanin in skin was dependent on the amount of ultraviolet radiation in a certain location, which Jablonski explains, "changes in skin pigmentation were adjustments to prevailing conditions. Because of the skin's importance as the body's primary defense against the environment, it has been under intense natural selection for most of our history."

Thus, race is just a product of human variation in response to changes in the environment, so classification by race becomes meaningless and a means to oppress certain groups of people.

At present, anthropologists view race as a social construct and part of a cultural identity. Though race has no impact on cultural behavior, and there is no true racial identity, the notion of race is deeply ingrained in our understanding of our own identity, leading to subconscious associations of race with culture, where people of a certain race are expected to behave in certain ways in order to integrate into the stereotypical cultural contexts of society. We ourselves impose categories with boundaries on this reality of human variation, still influenced by the impact of scientific racism used by governments and institutions as a form of oppression of people of color.

Although race has already been invalidated as a means of human biological variation, the lingering biases of race still contribute to the social categorization of human types in modern society, unable to break away from the conflation of race with culture and identity.

Comment